Malaysia continues to maintain its policy commitment to worker welfare, through its ongoing review of wage policies. In July 2023, Malaysia increased the minimum wage from RM1,200 to RM1,500, extending its applicability to micro-enterprises with a staff size of less than five. The minimum wage of RM1,500 was already in effect since May 2022 for companies with at least five employees. Minimum wages have progressed upwards over the last decade since the law was first implemented in 2013. The adoption of minimum wage policies, originally a practice in developed nations, has progressively gained traction in developing economies as they mature, underpinned by the core principle of ameliorating income inequality and ensuring that individuals attain an income level sufficient to meet basic needs.

Malaysia’s Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, improved from 0.431 to 0.401 between 2012 and 2014, a period soon after the initial implementation of the minimum wage law, suggesting some success of the regulation. The 7.0% improvement in the Gini coefficient between 2012 and 2014 was the second largest on record, with the largest at 9.3% between 1976 and 1979, a period marked by rising external demand, private investments, capital allowances, export incentivisation, rising savings and foreign capital inflows. These two periods of time represent scenarios that imply the success of previous growth-oriented strategies over the recent wage regulation in promoting income distribution.

Consequently, economic growth and development priorities ought to remain an overarching aim despite short-term targets in driving income redistribution. It is the fundamental role of policy to reduce potential negative externalities and social costs, which had already been partly addressed by minimum wages to reduce poverty. However, excessive wage advocacy may have the unintended consequence of demoting the narrative of productivity, which risks the creation of populist regulations that may stifle the private sector.

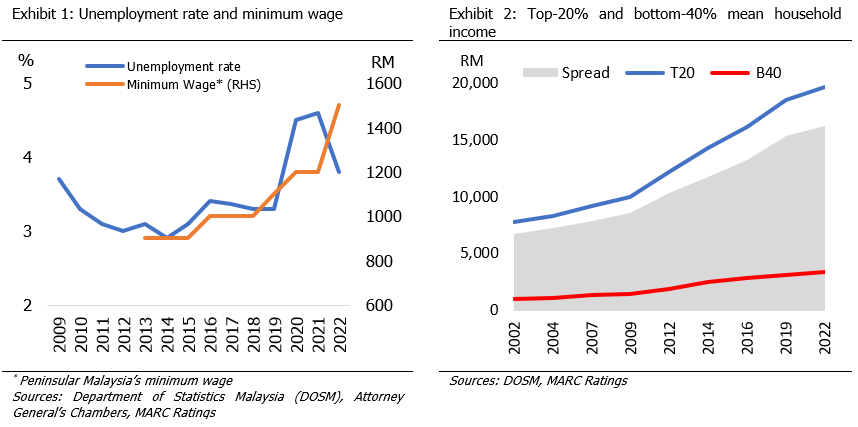

Of note, despite four successive minimum wage increases since its inception in 2013, diminishing marginal benefits in subsequent periods has become apparent, as indicated by the stagnating Gini coefficient at approximately 0.40 from 2014 to 2022. Additionally, the income spread, representing income inequality between the T20 and B40 income groups, has steadily increased despite the implementation of the minimum wage law. As such, there are inherent uncertainties regarding the efficacy of minimum wage policies or their extensions, such as the Progressive Wage Model (PWM), in stimulating productivity and employment.

Regardless of its form, any wage-price rigidity or intervention introduces complexities that are likely to raise regulation costs by the government and compliance costs by businesses. Furthermore, the corporate sector may reduce employment opportunities as businesses make compensatory adjustments to maintain earnings. Such deleterious adjustments could include a reduction in hiring, the reduction of pecuniary benefits, the substitution of labour for technology, the substitution of lower-skilled workers for higher-skilled workers with multitasking requirements, the hiring of undocumented workers and illegal immigrants, diminished investments in training, and the imposition of disproportionately higher output targets. Companies functioning with thin margins may have to close down, thereby reducing the number of available jobs. Employment opportunities and job stability will also be further reduced for individuals with skills and productivity levels that are not envisaged to scale up over time. Hence, minimum wages could have negative effects on marginalised segments of society that are poverty stricken with the least opportunities for education and advancement in the labour market, the group that the government intends to help the most. While other factors could be at play, we note that higher minimum wages improved the labour share of income in the economy, although this was accompanied by rising unemployment, even after excluding the period of the pandemic.

Wage-price rigidities will create difficulties in capturing the nuances of worker productivity and latent output potential, leading to pricing disparities within the labour market. Furthermore, as Malaysia pivots towards fostering economic complexity, characterised by the need for diverse skills and specialisations, the determination of progressive wage structures becomes increasingly challenging. Correlating wages with productivity is non-linear, particularly in complex, tertiary and service industries compared to basic manufacturing, which is incongruent with developmental goals to advance economic complexity and value-added sectors.

Higher wages can trigger ripple effects, including higher inflation, further raising costs for both businesses and individuals alike. Consequently, the government should focus on policies that raise economic growth through real productivity gains, which will in turn increase wages, expand employment opportunities and strengthen the purchasing power of the ringgit. Policies should also address labour market mismatches and incorporate adjustment policies to assist in balancing the supply and demand of human capital. Productivity gains can be driven by a dynamic and competitive labour market, facilitated by market-driven and global benchmarking practices in the management of human capital.