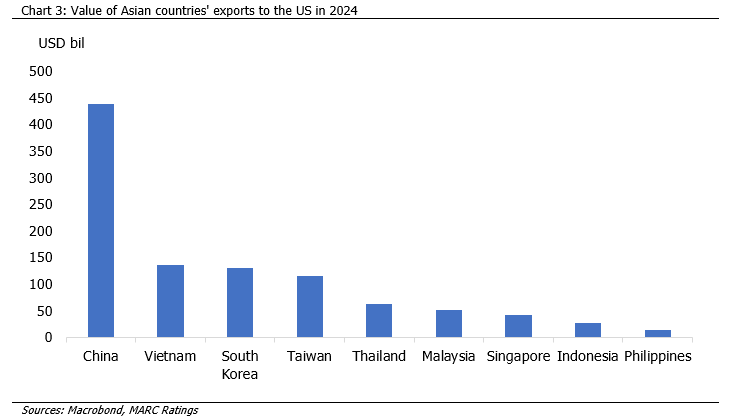

On April 2, the US government launched baseline tariffs of 10% on all imports to the US and reciprocal tariffs on trade partners which were deemed to have existing tariffs on the imports of US goods. This action is in line with the Trump administration’s ongoing and evolving policy on imposing trade tariffs amid rising economic nationalism. For now, the US has imposed a 24% tariff on imports from Malaysia, within the middle of the range of the reciprocal tariffs imposed on more than 180 countries. In addition, higher rates have been imposed on other countries in the region, namely Vietnam (46%), Thailand (36%) and Indonesia (32%). In the case of China, the primary target of US tariff measures, imposed tariffs have exceeded Trump’s initial guidance and may be subject to further escalation.

Reciprocal tariffs are inherently bidirectional and can escalate or de-escalate depending on the trajectory of negotiations. Given the evolution of tariff policies in both the US and its trading partners, there is scope for further negotiation and constructive pathways toward global trade agreements. First, specific methodologies or definitions used to calculate these direct and indirect tariffs, particularly the latter, are undisclosed, and the figures presented by the White House do not necessarily align with the actual tariffs imposed on US goods by other countries, suggesting that there is room for enhanced clarity on this framework. Furthermore, White House data suggests that the reciprocal tariffs currently imposed amount to roughly half of the calculated tariff levels, presenting considerable headroom for the US and its trading partners to adjust tariff levels.

Optimistically, Trump’s reciprocal tariffs have the potential to trigger a constructive negotiation process, akin to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) rounds or the renegotiating of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) into the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). However, realising such an outcome would require multilateralism, predictability, and shared goals to foster trust and move beyond deal-by-deal brinkmanship. On that note, Malaysia’s position in negotiations is strengthened by its role as Chair of ASEAN and its participation in multiple trade blocs, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Additionally, Trump’s invocation of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act can be challenged under the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Most Favoured Nation (MFN) obligation mandating non-discriminatory tariff levels between countries, among other regulations such as a due process for dispute resolution and the substantiation of these broad tariffs as an actual national security concern.

There are multiple mitigating factors that could lessen the impact of adverse scenarios arising from tariffs. Firstly, rather than halting trade, tariffs are generally expected to increase inflation, as costs are either passed on to consumers or absorbed along the value chain, and the possibility of tariff reductions on imports of US goods triggered by constructive reciprocity should not be ruled out. Furthermore, current tariffs are being imposed at a time when global interest rates have likely peaked, presaging a period of easier monetary policy which further widens the avenues for expansionary fiscal responses. Consequently, due to the availability of counterbalancing policy levers, the present trade war is more likely to lead to an economic slowdown rather than a major recession. Major recessions are usually precipitated by unexpected events such as a liquidity crunch, pandemic, or geopolitical calamity. In the US, while the odds of a recession have increased, the US economy continues to enjoy a strong labour market amid healthy liquidity conditions. Globally, the ongoing diversification of supply chains, driven by the recent pandemic and the introduction of tariffs during Trump’s first presidency, has better prepared the world to manage supply-side shocks.

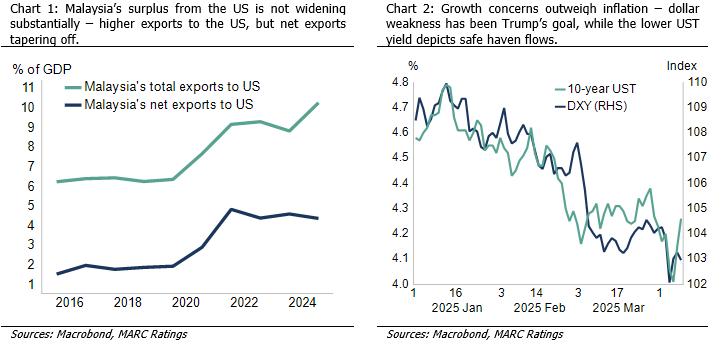

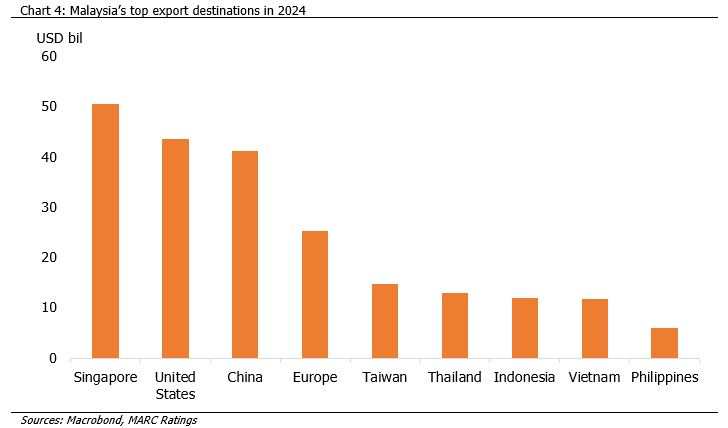

Our sensitivity analyses suggest that the impact of tariffs on Malaysia would be manageable, with growth forecasts likely to fall toward the lower end of the historical range observed during a standard economic cycle. Of note, Malaysia’s net exports to the US edged up to 4.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024, showing only mild fluctuations since the pandemic. Given the tariff shock coupled with a decline in regional and global growth, we estimate that Malaysia’s 2025 GDP could decrease by up to 1% per annum from our prior baseline growth forecast of 5%; furthermore, the adverse effects of the trade war are likely to persist into 2026. As such, the uncertainty factor is significant, as forecasts will be adversely affected if tariff retaliation is pursued and prolonged, and if separate negotiations between the US and other countries occur in a fragmented manner, leading to complex spillover effects. Nonetheless, Malaysia’s overall GDP is buffered by its strong, domestically driven economic base, at almost two-thirds of GDP. Another mitigating factor is the semiconductor sector being partially exempted from the tariffs; this sector contributes more than a quarter of Malaysia’s exports to the US.

Global protectionism tends to follow a cyclical pattern, and the reciprocal adjustment of tariffs can lead to price convergence between countries, potentially improving trade relations. Economies affected by tariffs in the real goods sector may respond by shifting economic development toward service industries, attracting foreign direct investment, and diversifying operations globally, whether in the US or elsewhere, to access new sources of demand and safeguard against supply chain disruptions caused by evolving trade protectionist policies. Apart from the intention to raise the growth of domestic US industries through reshoring, an additional subset of tariff policy is to increase US government revenues; it is likely that some achievement of these objectives to enhance the US economic position will eventually limit the extent of the ongoing trade war.