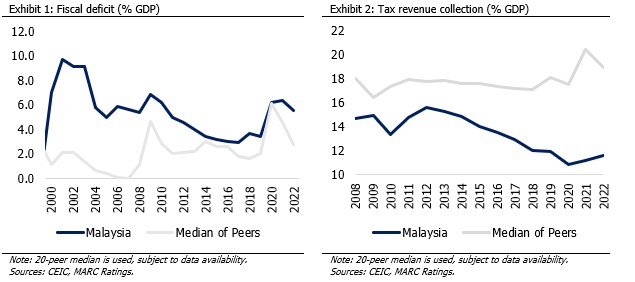

Malaysia continues to maintain its long-term commitment of fiscal consolidation to enhance debt sustainability. In terms of the government’s fiscal balance, this has remained largely stable, excluding during the pandemic period. Over the 10-year period from 2013 to 2022, Malaysia’s fiscal deficit averaged 4.2% of gross domestic product (GDP). Excluding the COVID-19 fund, Malaysia’s fiscal deficit would have been averaging at consistently below 4% of GDP. As such, the government’s goal to achieve a 3.5% fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratio by 2025 appears pragmatic and achievable.

However, the dynamically evolving landscape of global risks, including climate-induced natural disasters, tightening of global financing conditions, and geopolitical tensions, accentuates the paramount importance of fiscal prudence. The imperative to raise financial reserves as a safeguard against these unforeseen contingencies cannot be overstated.

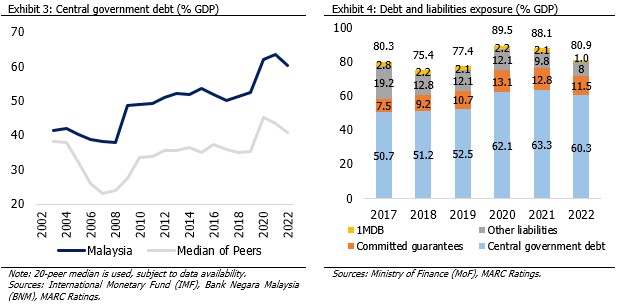

Other measures of public sector finances provide further insights into the progress of Malaysia’s debt management. Total government debt, including contingent liabilities, had consolidated below 80% of GDP before the pandemic, at 77.4% of GDP in 2019. However, due to investments in public healthcare during the pandemic, the total government debt including contingent liabilities-to-GDP ratio peaked at 89.5% in 2020 before declining to 80.9% in 2022. This ratio is expected to continue improving over time, to under 80% of GDP in the near term. This is due to debts related to 1MDB maturing, such as the USD3 billion which matured in March 2023.

In contrast to peers with similar or closely aligned international ratings, Malaysia’s debt-to-GDP ratio has remained relatively elevated, a measure requiring improvement. Malaysia’s debt-to-GDP ratio in 2022 stood at 60.3% against its peers’ median of 40.9%. Furthermore, the pace of debt accumulation in Malaysia was slightly higher compared to peers, adding 7.3% to the debt-to-GDP ratio for the 10-year period from 2013 to 2022 while the peer group’s median increased 5.3%. Thus, Malaysia must maintain its ongoing efforts towards the formal institutionalisation of various debt metrics, such as the intended tabling of the Fiscal Responsibility Act.

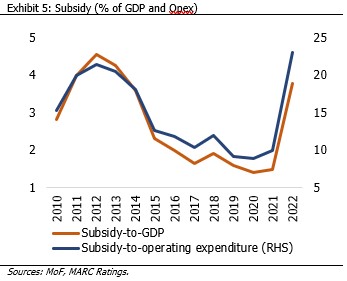

The prospects for fiscal improvement against its peers hinge on the effective execution of government policies. Notably, policymakers have expressed intent to curtail subsidies; Malaysia’s subsidy-to-GDP ratio reached 3.8% in 2022, compared to the five-year average (2017-2021) of 1.6%. Subsidies have risen and remained a substantial portion of the government’s operating expenditure, accounting for 23.0% in 2022 from an average of 10.0% over the previous five years (2017-2021). Excessive spending on subsidies constrains the government’s capacity to redirect funds to other critical public service areas. To foster fiscal consolidation, a paramount focus lies in bolstering tax collections and compliance, particularly given the decline in Malaysia’s tax revenue-to-GDP ratio from 15.3% in 2013 to 11.7% in 2022. Contrastingly, peer nations experienced an increase in this ratio from 17.9% to 18.9% during the same period.

While theory asserts that the Goods and Services Tax (GST) is regressive and places a burden on low-income households, tax sufficiency to sustain Malaysia’s extensive social assistance initiatives is of utmost importance. These programmes encompass a wide array of subsidies for essentials, including but not limited to food, fuel, electricity, healthcare, housing, and education. Therefore, maintaining a robust revenue stream, through mechanisms like the GST, is critical for the continued provision of these crucial welfare benefits to the nation’s populace.

According to 2022 data from the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), approximately 174 countries and territories, including many with lower income levels than Malaysia, have adopted the GST or a similar consumption tax model. As such, the abolition of the GST in Malaysia in 2018 by the previous government places the country in the minority of those without GST. Furthermore, the removal of GST back then has been commonly perceived as a populist action rather than a decision rooted in economic logic, leading to an adverse impact on Malaysia’s policy credibility and stability. It is therefore crucial to address and rectify the consequences of this previous policy reversal. To complement Malaysia’s existing social assistance programmes, concerns about the potential impact of GST on low-income households can be alleviated through measures such as targeted exemptions for essential goods and the implementation of a tiered tax rate structure.

In addition, enhancing the sustainability of debt through the raising and broadening of the tax base is a prerequisite to upholding investor confidence in Malaysia’s debt markets. This, in turn, safeguards the nation’s prospective capacity to secure funding for vital public services and investments, and mitigates burdening future generations with elevated debt levels and tax obligations. Moreover, the trajectory of the Malaysian ringgit is significantly influenced by debt management credibility. The preservation of confidence in the capital markets and the stability of the national currency constitute fundamental prerequisites for economic prosperity. Without such stability, there exists the potential for distortions in the behaviour of economic agents, thereby inducing a state of cautionary hysteresis.

Our analysis suggests that Malaysia could potentially halve its fiscal deficit by gradually restoring its subsidy-to-GDP ratio and tax revenue-to-GDP ratio to their respective 10-year averages (2013-2022) of 2.4% and 12.8%. To this end, the implementation of consumption taxes such as the GST or Value Added Tax (VAT) is recommended. These tax measures, administratively efficient and designed to reduce avenues for tax avoidance and evasion including from within the informal sector, are crucial enablers of the optimisation of Malaysia’s fiscal and debt position, as well as the nation’s economic future.