In the previous parts of this series pertaining to fiscal sustainability, we have discussed the country’s revenue, expenditures, and general balance sheet items. In this final part, we delve beyond traditional debt metrics to offer innovative insights into the country’s fiscal health.

Fiscal sustainability is often benchmarked by debt-led indicators; however, this runs the risk of forming a narrow analysis. By broadening the scope and innovating the metrics involved, a more thorough view of the nation’s fiscal position could be attained. Benchmarking fiscal health by measuring the national net worth — aggregating the country’s contingent assets and liabilities — offers a clearer view of fiscal sustainability. Beyond liabilities, contingent assets, which are often overlooked, are also important to provide a balanced perspective. Incorporating contingent assets into fiscal assessment enables a more holistic understanding of the government’s resources available in support of the country’s sovereign credit rating. Additionally, it is important to assess economic growth relative to interest rate levels to gain a better understanding of fiscal sustainability.

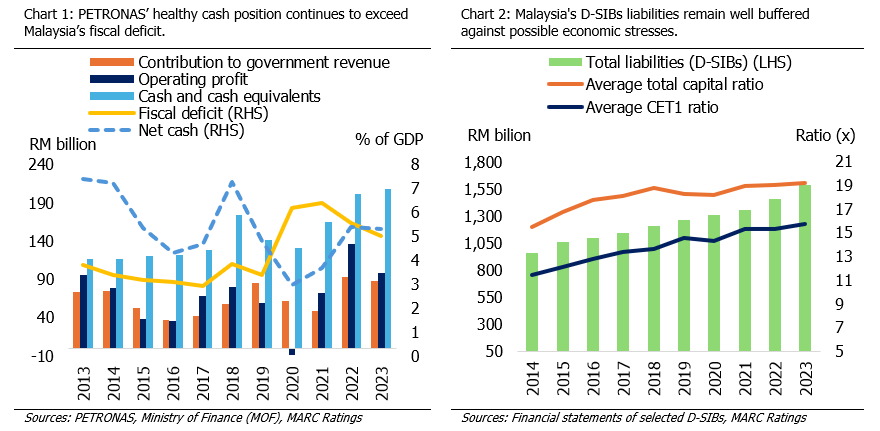

Primary examples of Malaysia’s contingent assets, which can provide additional resources to stabilise the economy when needed, include its national oil corporation and government-linked investment corporations. Petroliam Nasional Berhad (PETRONAS), for instance, contributed RM85.7 billion to government revenue in 2023 and plays a dominant role in the domestic economy. Additionally, liquid assets including funds, cash and cash equivalents exceeded RM220 billion in 2023, equivalent to 12% of Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP), exceeding Malaysia’s fiscal deficit of 5% as at 2023. PETRONAS’ financial strength is a critical pillar supporting Malaysia’s fiscal position, and this is further reinforced by the country’s sizeable sovereign wealth fund. As such, Malaysia’s total contingent assets are estimated as sufficient to cover government-guaranteed debt.

Conversely, contingent liabilities can include the financial obligations of government-linked corporations, particularly within the financial sector. The relationship between sovereign ratings and the banking sector exists within a reflexive feedback loop: changes in a country’s credit rating can affect banks’ funding costs and risk assessments, while the health of the banking sector can, in turn, influence the sovereign rating by impacting overall financial stability. Notably, Malaysia’s two major banks — both of which are majority-owned by government-linked institutions — collectively held nearly RM1.6 trillion of liabilities in 2023. Due to their size and importance, these banks have been classified as domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBs) by Bank Negara Malaysia. Of note, these institutions are well-capitalised, boasting a total capital ratio of 19.2% and a Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio of 15.7%, both of which exceed the regulatory minimums of 9.0% and 5.5% (non–D-SIBs: 8.0% and 4.5%). We further note that the recognition of contingent liabilities as risks in the banking system enhances fiscal surveillance but does not imply the likelihood of crystallisation of such liabilities.

Another future liability to consider is the government’s pension obligations. This reached RM22.5 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach RM25 billion in 2024. In 2022, the pension fund size was estimated at RM169.8 billion, generating around RM6.0 billion in investment income, but remained insufficient to fully cover the rising annual pension payments. To address this, the government has introduced reforms, including enrolling new public sector recruits into the Employees Provident Fund instead of traditional pension schemes. Additional measures, such as raising the retirement age and increasing employee contributions, could further improve the fund’s self-sufficiency and ease long-term fiscal pressures.

An alternative assessment to fiscal sustainability, beyond the use of conventional fiscal deficit and debt ratios, can be made through an understanding of economic growth relative to interest costs. Higher economic growth relative to borrowing costs results in gradual passive deleveraging, naturally lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio. Malaysia’s economic growth-interest rate differential metric (Differential) is positive and averaged 0.2 from 2014 to 2023. We note that the Differential turned negative at -0.2 in 2023 due to lower-than-expected domestic economic growth. Despite this, Malaysia’s Differential in 2023 remains healthier than those of advanced economies (-1.8), emerging economies (-1.9) and ASEAN economies (-0.3).

Looking ahead, Malaysia’s fiscal deficit target of 3.0% by 2026, as discussed in the first part of this series, remains challenging but achievable. We estimate that targeting a Differential of at least 0.9, while limiting debt growth to 8% per annum, can materially improve Malaysia’s fiscal deficit. Malaysia is on track to meet the Differential target based on current projections, which is encouraging. However, raising economic growth remains essential to further improve the Differential and ensure long-term fiscal sustainability.

This press announcement is the third and final in a multi-part series discussing our opinions over Malaysia’s fiscal health and considerations to be made in achieving fiscal sustainability.